This is a period of significant anniversaries linked to Nelson Mandela, as it is 60 years since he was sentenced to life imprisonment in South Africa and 30 years since, in a momentous transformation, he was elected as the country’s first post-Apartheid president.

Mandela was particularly revered in Ireland, where he was rightly regarded as the most important international figure of the second half of the 20th century, and, even 11 years after his passing, his influence remains strong to this day.

He had a number of close Irish connections after gaining his freedom, and among the most unlikely was his relationship with Tony O’Reilly, who was effectively the main instigator of the economic boom known as the Celtic Tiger and enjoyed extraordinary business success across three continents before his death earlier this year.

It would be hard to imagine two more different individuals, but they revelled in each other’s company, as I discovered during an absorbing encounter at O’Reilly’s palatial Dublin residence just under a quarter of a century ago.

From the moment that a deferential butler opened the front door of the spectacular Georgian town house in Fitzwilliam Square, which dated back to the 1790s, before ushering me to an upstairs drawing room lavishly decorated with elegant art works, it was quite an occasion.

O’Reilly, at that stage aged 63 and Ireland’s richest person, with the Independent News and Media group among his multi-national portfolio of companies, had generously decided to invite the editors of the country’s daily and Sunday newspapers, north and south, to a private lunch with his old friend Mandela.

It was difficult to know what to expect from O’Reilly, who was noted for both ruthlessness and philanthropy, but, as we awaited the arrival of our distinguished guest, he was charm personified.

Tall, tanned, immaculately dressed, and every inch a Master of the Universe of the kind described in the acclaimed Tom Wolfe book of the era, Bonfire of the Vanities, he began by offering his thoughts on some personalities who were making headlines in Ireland.

O’Reilly was a hugely talented mimic, and, with a glass of impossibly expensive dry white wine in his hand, performed uncanny but occasionally unflattering impersonations of the likes of Charlie Haughey, Bertie Ahern, Bono and Gay Byrne.

It was a bravura performance, interrupted only when an aide whispered in his ear that it was time to adjourn to the enormous dining room, just before the suitably grand entrance of Mandela, looking much younger than his 80 years, with his natural gravitas complemented by a stunning rainbow shirt as he greeted his host with obvious affection.

While Mandela had the equivalent of an aristocratic background, before spending almost three decades in prison and then emerging as president of a reformed country, retiring from office a year previously, O’Reilly was raised by a single parent in lower middle-class Dublin in advance of a stellar sporting and business career which won him enormous fame and fortune.

O’Reilly’s commercial and political initiatives in South Africa brought the pair together, and, although they plainly held sharply contrasting positions on many matters, there was no disguising the warmth between the two men.

It was striking to hear Mandela movingly drawing on his experiences in the notorious Robben Island jail after a trial in which the prosecution had demanded the death penalty, explaining why revolution had been necessary in South Africa and quietly advocating a new world order, while simultaneously displaying his respect for O’Reilly, who had the full status of a corporate titan.

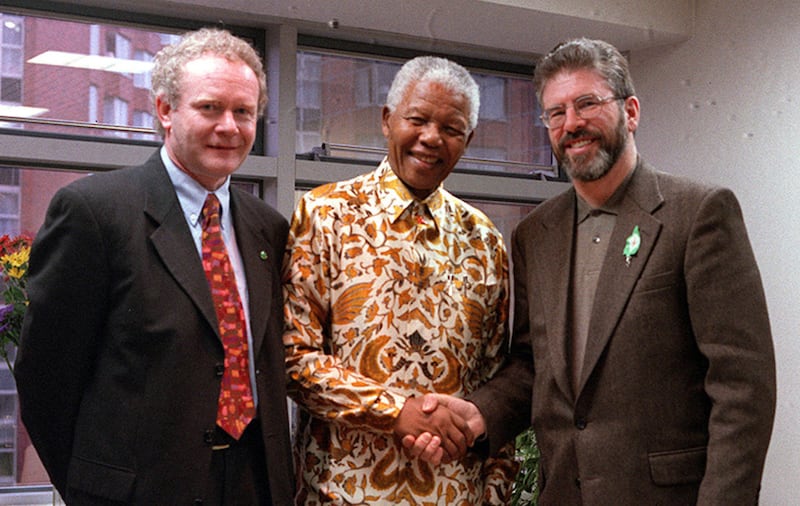

As we spoke over lunch, with O’Reilly magisterially seeking questions from around the table, it became clear that Mandela maintained regular contact with the Sinn Féin leadership and was an even stronger admirer of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness than had been previously hinted.

Among the unresolved major issues after the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 was decommissioning, and Mandela calmly and firmly declared his opposition to any idea of IRA disarmament – although it was subsequently to become a reality – while O’Reilly, whose Dublin newspapers were then hostile to all shades of northern nationalism, and who accepted a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth the following year, smiled inscrutably.

Mandela’s global reputation remained largely intact for the rest of his days, but O’Reilly’s vast financial empire was to collapse in complex and dramatic circumstances before his health declined and he eventually died last May.

History can judge them, but I will not easily forget the afternoon I spent in their unique company.

n.doran@irishnews.com

It would be hard to imagine two more different individuals, but they revelled in each other’s company, as I discovered during an absorbing encounter at O’Reilly’s palatial Dublin residence just under a quarter of a century ago